Héctor Hinojosa Zozaya, house on Samuel Ramos Magaña 27, view from the garden

Awaiting its forthcoming demolition, the house numbered 27 along a short street named after the philosopher of art Samuel Ramos Magaña grows conscious of its nearness to the ground, seeing that a taller life will take its place to at last level the above vista potholed by its two stories. It is among the buildings that remain squat in a block where shoot up apartments serving Mexico City’s swelling population, a market taken on by the sector of real estate which the Spanish language draws up as bienes raíces or bienes inmuebles. If taken faithfully to their Latin source, the pairs of words move the idea of rooted or immovable goods and act as antipodes to the bienes muebles. As such, they draw forth a dualism deliberated upon one’s adherence to the ground, if not, one’s wakefulness to being furnished, moved, and to where, as per the artist Jimmie Durham.1 Closely, those like the architectural historian Louise Noelle Gras believe that buildings are verily moving, in the sense like texts, which if enriched by the critic’s power to behold, radiates to whoever visits them.2

![]()

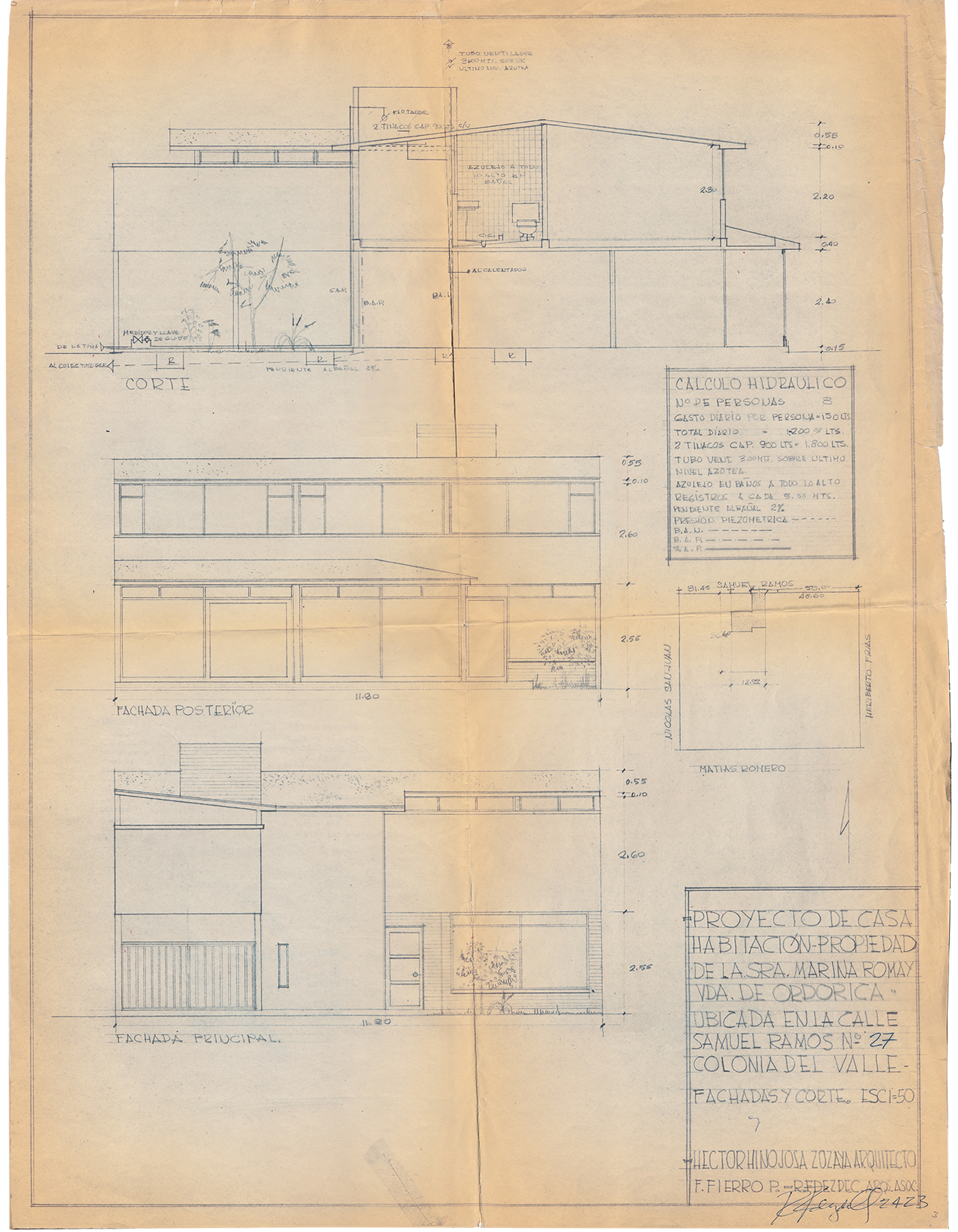

Héctor Hinojosa Zozaya, blueprint of house on Samuel Ramos Magaña 27, 1966

Among the genuses that will pass away hither are the parqué (marqueteried flooring), terrazzo (floor treated with chips of marble and granite set in concrete), gotelé (stipple ceiling), techo de teja de barro (clay tile roof), fachaletas de barro tipo ladrillo (brick-type clay facades), and azulejos (glazed tiles), durable derms of a domicile over, under, and around which, stray creatures including peoples, cats, worms, bugs, mosquitoes, and spiders, have passed parts of their brief and fugitive lives. The sundry surfaces whose work include heating, drying, spreading, dripping, inlaying, overlaying, and repeating, nuance the social climate of the house’s chambers. Take for example the cuarto and baño de servicio (maid’s quarter and bath) whose terrazzo flooring correlates with that of the downstairs cocina (kitchen) and adjoining desayunador or antecomedor (dinette) and differs from the wooden parqué of the three recámaras (bedrooms) and the azulejo of their baños. It is such disparate skins which too hold the house’s frame that is so rectilinear that its upstairs tenants for the most part move perpendicularly. They are led by the margins of narrow doors and halls, and a half turn staircase connecting the ground floor vestíbulo (foyer) to the second-floor landing, this latter at certain times turn pitch dark when all five doors which rim it close shut. Here, on the upper floor, the sensation is hermetic as it is uncooperative to the modernist tendency to construct space that flows between different rooms3 and makes indistinct the often-coupled indoors and outdoors. Instead, what persists is a domestic life requiring the utmost privacy and intimacy,4 the desire for such the architectural historian Enrique Ayala Alonso traces to a social distinction, which beginning in 17th century Mexico was coveted by families living with servants with whom they did not want to mix.5

Héctor Hinojosa Zozaya, blueprint of house on Samuel Ramos Magaña 27, 1966

The second-floor landing turns right to the the recámara principal (master bedroom), most spacious among three in a row and under which spreads out the comedor (dining room-suite) contiguous with the estancia (living room), areas usually separated by load-bearing walls in colonial mansions, but here enclosed in partitions.6 Still upstairs and turning to the left opens to another corner which leads to a hall tapering to the other end of the house’s L layout where cuarto de servicio and tendedero (area for drying clothes) keep out of their employer’s sight. Instead of equal scale, the little quarter hovers closest to the street and above the garaje (garage), the latter sitting next to the lavandería (laundry area) occupied by tilichero (junk room), lavadora (washer), secadora (drier), and tinaco (water tank). This little unroofed space, however marginal and which the blueprint christens ‘vacío,’ likely acts as a courtyard for the servant. Touching on the enclosure’s placement inside a house, Ayala Alonso for example reports how starting in the late 19th century in Mexico, the central patio, by which the house receives light and air, turned into a covered spacious lobby7 Uneven in terms of spaciousness, flooring, and lighting, the house on Samuel Ramos Magaña 27 keeps alive the social stratum that persists today but which architects at present ought to put an end to.

Entrada of the house showing two of four windows facing the street

The gestation of the house lasted some five years where sometime through the topographic survey of the property in 1962, the approval of its construction license in 1966, and its likely completion in 1967, the name of the street changed from 2a Comisión Monetaria to its present designation. The house’s architect was Héctor Hinojosa Zozaya with whose casa Fabre in El Pedregal (1958)8 and templo de Nuestra Señora del Buen Consejo in Polanco (1961), the house employs sloping roofs and black iron to frame its glass windows. This tendency may be held close to Hinojosa’s pupilage to the admired architect José Villagran García of whose functionalist credo he was a follower.9 In Mexico, functionalism and rationalism’s social motives beget the unidades habitacionales, multifamily housing projects which stretched the edifice’s height at the risk of earthquake’s ruination, and which is a cousin to the omnipresent apartment. Simultaneous to the fashion of those in metropolises worldwide, it is the lofty species of the departamento or apartamento that leaves no neighborhood unturned. They take their name from the Latin ‘to divide’ or ‘to set apart’ and oust the nether casa to take over largely cut premises of nuclear, upper middle-class, single-familism, perhaps most bodied forth in the capital by Del Valle. A residential and divisionary suburb founded for the aristocracy to build their country villas during the Porfirato (1876–1911), it was hitherto known as the Campestre del Valle, countryside to the nucleus of what is today Tlacoquemecatl del Valle. Juan, the third-generation owner of the property, shares that his grandfather told him how at the time of the property’s purchase, there was nothing in the area, not even pavement nor street names, except for cows or horses grazing the fields. By nothing, he must mean the nonentity of an upright architecture or thoroughfares plied by the automobile contrived by an urbanite, leaving out the life forms of, among others, cattle, stallion, and grassland to its rural void or nothingness. This anecdote Juan thinks side by side the next-door apartment which upon its construction started casting down its shadow so as to block the sun from landing on a lot day in, day out deep in the dark. Because of its close to airtight plan, which draws in the sparing appearance of windows, the house admits less light and insulates a low temperature, one felt most in the cuarto de servicio on whose slim and overhead horizon of an aperture enters the afternoon light just for a little while. That a domestic helper receives little light in a room that was just years prior open air, points to the oppressive ceiling by which architecture supposes one should take shelter, come into contact with the elements, and submit the body to another. After all, architecture is not just the life of a building, it is besides the lives with which it lives. Their bond may be made out by way of the window’s self-queried world as to how much of the outside it wants to bring in, thinks Teodoro González de León,10 who with Villagrán García, formed part a generation of modernist architects abreast of its discipline’s historical, social, and theoretical systems.

![]()

Enrique Guzman Sañudo, topographic survey of the adjoining lots along calle Samuel Ramos Magaña, 1962

For the reason that on almost half of its 440-square meter property grows a garden, Samuel Ramos Magaña 27’s distance to the ground is not only earthward. If the house takes up the perimeter’s space on the side of the street, there by the garden’s corner, its residents have stood during the mornings so that their flesh take in the sun already high by nine in the morning. On this very site, a rubber tree once stood ethereally before it was struck down by lightning, remembers Juan. He supposes that the tree was among the tallest bodies in the area, a lore shared to him by the gardener Daniel who since the age of seven, has watched take to the air the garden’s thriving trees which he occasionally trims to the day. He is ever wary not to fell them, given the regulation set by the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente de la Ciudad de México which strictly penalizes the cutting down of trees including the pruning of their roots, non-native and invasive species like the ficus included. It seems that between house and tree occupying all but the same soil, it is the latter species that will sardonically remain unmoved, not for its roots which bury deep, but perhaps, on the grounds that the life of a house is often regarded to be without them.

![]()

View of the garden from the middle bedroom

From the edges of the garden, one affords a view of the three rooms above the little door such that the latter works like a slim portal for species otherwise restricted from the street’s end to enter. From this side, the cuarto de servicio assumes a rearness and thus gains exemption to a wide view of a yard reserved for its owners andwhere roam freely birds and squirrels. On this address, more species than usual share the terrain even where between building and garden rises a glass, the material deemed by its critics to be the antithesis to the condition of refuge.11 At night, the glass reflects so brightly light sources ignited by humans deep in activity, such as a laptop screen, kitchen light, or chandelier, that the life of the garden disappears into the dark from the inside. Come morning, the sun rises in the face of its light hardly landing at a residence whose roots, may be, the passing of property.

1 Jimmie Durham, Entre el mueble y el inmueble (Entre una roca y un lugar sólido) (Mexico: Alias Editorial, 2007), 21.

2 Louise Noelle Gras, “The Power to Behold,” in On the Duty and Power of Architectural Criticism, ed. Wilfried Wang (Texas: University of Texas Press, 2022), 20–21.

3 Ibid; Enrique Ayala Alonso, La casa de la Ciudad de México. Evolución y transformaciones (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1996), 108.

4 Enrique Ayala Alonso, “Espacio en la arquitectura moderna,” in Posrevolución y modernización. Partrimonio del siglo XX, ed. Marco Tulio Peraza Guzmán (Mérida: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, 2007), 42.

5 Ayala Alonso 1996, 63–64 and 86.

6 Ayala Alonso 2007, 42.

7 Ibid, 97.

8 César René Moreno Soto, “Casa Fabre: Héctor Hinojosa Zozaya,” Bitácora Arquitectura, no. 31 (2015): 137.

9 Alfonso Pérez Méndez and Alejandro Aptilon, Las casas del Pedregal: 1947–1968 (Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2007), 161.

10 Teodoro González de León, interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist, in Conversations in Mexico, ed. Karen Marta (Mexico: Fundación Alumnos 47, 2016), 134.

11 Ayala Alonso 2007, 43.

blueprints © Juan Ordorca Fernándezphotography © Kiko del Rosario