Ileana Lee (born 1951 in Saravia, Negros Occidental, PH; lives in Honolulu, Hawaii, US) thinks of her sources as wells, hinting at a connection with space that extends far down but also up into the sun and skies under which she follows fortune’s call, whether in Bacolod, Quezon City, Los Baños, Columbus, Chicago, Berkeley, or Big Island. A particular place turns out to be significant such as when she casts her mind to the childhood home she shared with a father who was a warehouse manager-cum-traveling flautist, a mother who taught home economics, and a crafty older brother. Just the same, it was a botanist aunt who ocassionally took her to the forest to gather specimen, and for that trained Lee to pay attention to her surroundings, counting domestic spaces as they’ve been put together by women.

To this, Lee admits to migrating the grammar of other interests, such as film, poetry, and music, into conceptual and graphic areas further considered with teachers such as Roberto Chabet, Ofelia Gelvezon-Téqui, and Larry Alcala at the University of the Philippines where she studied editorial design, as well as with Susan Dallas-Swann at the Ohio State University where she kept at her printmaking and performance practices. The work of art suggests rather than defines, believes Lee, alongside a manner of living that is available to the passing moment and which lends itself patiently to much evocation.

To this, Lee admits to migrating the grammar of other interests, such as film, poetry, and music, into conceptual and graphic areas further considered with teachers such as Roberto Chabet, Ofelia Gelvezon-Téqui, and Larry Alcala at the University of the Philippines where she studied editorial design, as well as with Susan Dallas-Swann at the Ohio State University where she kept at her printmaking and performance practices. The work of art suggests rather than defines, believes Lee, alongside a manner of living that is available to the passing moment and which lends itself patiently to much evocation.

Kiko I now remember your master’s thesis from 1986 which you titled “Living Space,” and in which you wrote that “Living is the necessary condition; and artmaking is its counterpoint.” Do you continue to regard this view to be true?

Ileana

Well that was a long time ago. (laughs) There’s the source: the well. Where you live, the things you see and experience—those are the elements that help you create, so that you have a source—a well—to generate from.

Kiko When you say living space, do you refer to the world at large?

Ileana Yes, the world at large and the environment where you’re situated. And when you live in another place, that is another source. All the elements around you become the material from which you create.

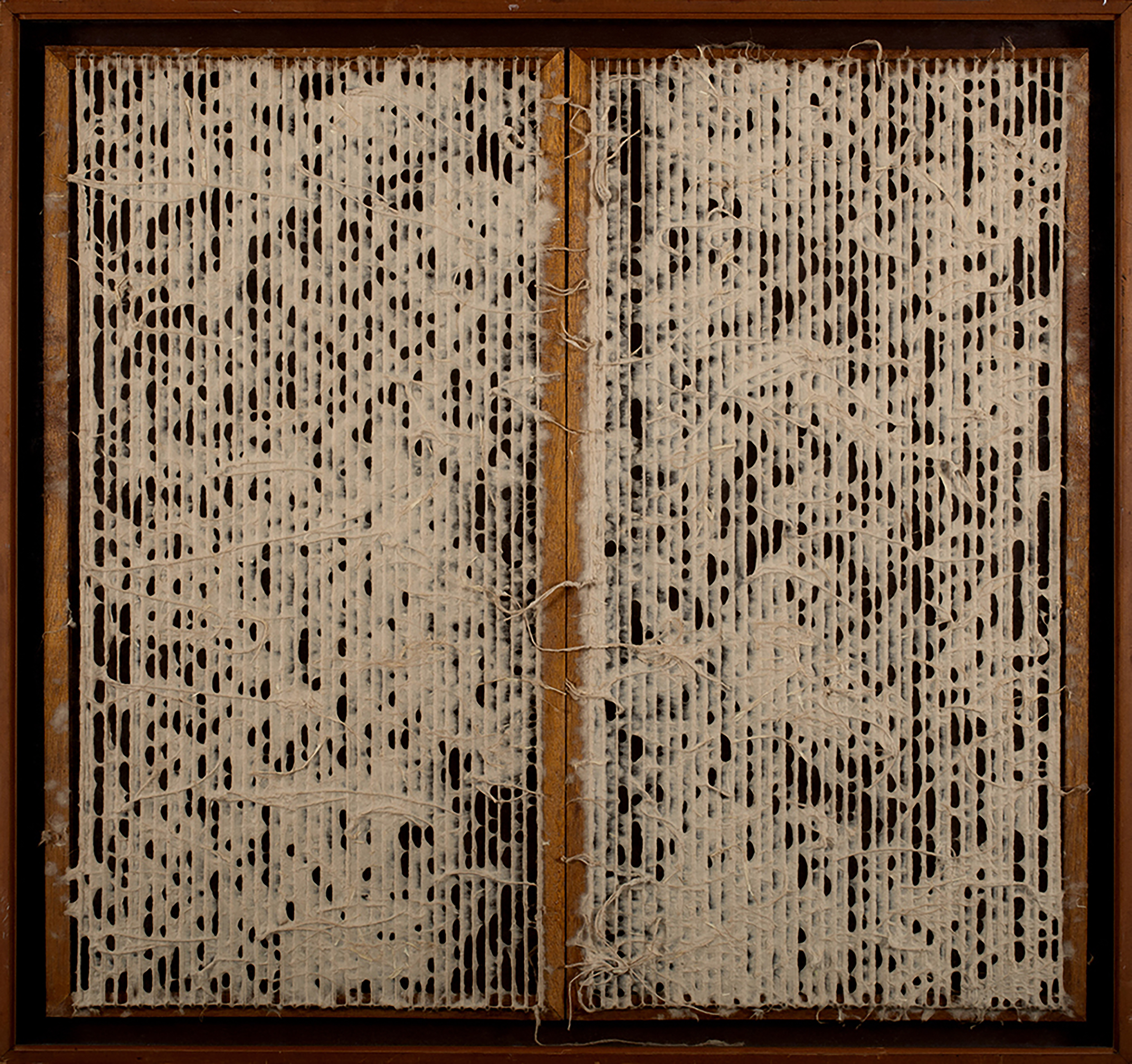

Kiko About your 1983 work Light Pores, you wrote—and I have always been struck by this:

“I remember when I was small, I was lying in bed looking at the specks of light that flickered through the nipa roof as the banana leaves rustled. I consider this print as an envrionmental installation in that it created an impressionistic atmosphere depending on the time of the day, which gave life to the print like a pulsating kind of ambience.”

I’ve always thought that staring or looking fixedly at something is vital for artistic work. Is this a view that you share?

Ileana Yes, because when I did that, at first I was working with those holes. It connects to my childhood.

Kiko Is this something that you do often, just look or stare at things?

Ileana Yeah, like one time I was at the studio. And I had this piece of wood and I didn’t know what I was going to make out of it. I sat near the window—there were these big windows—and when you looked out there was the Banyan tree, and it was noon, so there was a cast of shadow from the branches and leaves. I was thinking, “What image would I carve?” And then I saw the shadow right there and I said, “Alright I will make a woodcut of that shadow.” Sometimes it’s very quick.

And in the late ‘60s, I was having insomnia and I remembered when I was in high school, I could not understand poetry. So I started going to the library and borrowed the book we used in high school and I thought maybe I should retrace: why couldn’t I understand it? I was reading English literature and then I said, “Oh, I kind of understand now.” Now I can relate to what this poet was saying. So in connection to the shadow, I was making this haiku series. (points to works in her studio) I would put imagery in the extremes and would have space in between, like a haiku. I usually work miniserieses. It might look like “she’s kind of everywhere. She does this and that.” I don’t work linearly. I don’t work in that one way. Once an idea is cemented, then I create a series of that, at that point, and then another idea comes and then I can make variations of the particular idea. So it usually starts with a visual, a particular form.

Kiko I’m thinking about how you choose not to work linearly.

Ileana I had a still life series in the ‘90s. I used to live in an industrial area. There were a lot of scraps of wood around and so whenever I saw these wood—I never had a car—I would salvage them and out of those I created still life series. They are cuts of wood and I would join them with vase-shaped [inaudible].

Kiko And how about your close relationship with the envrionment and your surroundings? How is that relationship like under the ecological crisis that we are going through at the moment?

Ileana I did some cut wood in the ‘90s for an installation. This time around, I chose the oldest printmaking process, which is the woodcut, and I specifically chose a magazine that had Hawaiian images, from landscapes to flowers—whatever that’s Hawaiian—aquatic fish, whatever. So I get those magazines, now printed digitally, not offset anymore. So I cut them up in squares in an exacting way and I collaged them on top of the woodcut. So the idea is: here is a printing process, the oldest one, and now it looks like it’s pixelating. That’s my statement. In a way, it’s an invasion of the traditional printed image and I make sure it looks like a traditional still life, not abstracted extremely.

Kiko You’re drawn to the still life.

Ileana While I was still in California, I took videos of women cooking, or laundrying, you know, domestic chores. And I made installations of those, and it connects to “What is domesticity?” and that connects to the still life and images of home—a vase of flowers in the house. I have curtains too which I exhibited at West Gallery one time. They are curtains that were printed, like upholstered images.

Kiko You were born in Saravia, Negros Occidental in 1951, which is a town nestled in between Victorias, home to the Ossorio family’s mill, and the upperclass enclave of Silay. How would you say has Negros calibrated you so that you would arrive at becoming an artist?

Ileana Oh, I don’t know, but when I was younger I would always draw. I would be playing outside and all of a sudden, I wanted to go inside. And I would have this small set of watercolor and I would just sit down, get a bond paper, and just paint. I always drew, I remember. We had this blackboard at home. It’s a small, you know, like a kid’s blackboard on which you put the chalk. And I was the one using that. I would go there and draw something... for a day... and then the next day, I looked at it and would erase it and draw another thing. It was constant, it was there, even when I was younger. And then I had an older brother who was also artistic. So when I was small, he had some class projects and he would do papier-mâché, and I was always there watching or helping him. I remember he did a Roman helmet. I was exposed to him doing, creating, and so sometimes I would also copy pictures and draw. Those were my initial stages but as a kid, I was always drawing.

Kiko I know that your sister is the UP [University of the Philippines] librarian Verna Lee.

Ileana Yeah, we are seven. But the older brother I mentioned to you—he died when he was 25.

Kiko Oh, I’m sorry.

Ileana He was creative: he cooked, he did carpentry. He went to Don Bosco [Technical Institute, Victorias] so he learned carpentry. For one of his projects, he assembled a jeep with another mechanic who taught him. They bought parts of the jeepney. They bought a Toyota motor and assembled it. He was very handy. So, but then, he had a heart failure. It was a sudden death. He was one of those who I remember I was exposed to.

Kiko And your parents? What were their jobs?

Ileana My father migrated to the Philippines. He’s from Amoy, in Putuo island. There were so many Chinese from there who migrated and settled to the Philippines. He’s a musician actually. He played the Chinese flute. When we were growing up, he worked in a hardware store—daytime, 8 to 5.

Kiko What did he do there?

Ileana He was assigned to the warehouse. He was like the warehouse manager. He took orders and deliveries. It was not far from our house. That hardware store was a block and a half from our house. So when we went to downtown, we passed by the hardware, see him standing there waiting for the deliveries. (laughs) So yeah, it was a hardware store in Bacolod. It was a big hardware store for a provincial city, I guess. So anyway, at night after work he would come home. He would hit a big kettle of water. And while waiting for that to boil, he would sit at the end of the bed, already practising his flute. So then he would shower, eat dinner ahead of us while we were still doing our homework. My mother was still in school—my mother was a home economics teacher. And then he would linger a little bit, talk to us a little bit, and before we knew it he was gone. He goes to the music house. We call it a music club, but it was a music house. They had a Chinese maestro. And what we know is that, that Chinese maestro came from the Mainland, was invited by the Chinese business community in Bacolod. They financed him, paid for the house. Because I think music was important for the Chinese community, so the business people, and my father went there with other musicians from Bacolod and they would practice and made their gig there. I remember, I went with him one time to a Chinese temple and watched him play there. They performed funeral and festival music.

I remember when I was already at UP, my mother told me that my father was going to Manila to perform in Chinatown. So I would look for him there. They stayed at a hotel. Other groups would converge in Manila around October, the Moon festival. He played the Chinese bamboo flute. That’s what they would do for a week maybe, he would be there, and then he would come home.

Kiko You were already living in Bacolod then?

Ileana Yeah, we were children then. He would just go out and practice and come home late at night and then the next day would come to work. But what I remembered was that they would travel to Manila.

Kiko And your mother?

Ileana My mother was a home economics teacher. She taught at the private school in Bacolod: West Negros College. They had a home economics department, so they had this practice house where the students would stay-in and do the activities of the house: they baked, cooked, whatever.

Kiko Did they ever encourage your artistic inclinations?

Ileana I think my mother knew that I had those. But I remember one time when I was small, they asked, “What do you want to be?” “I want to be a painter,” I said. And then she said, “Not a painter because you’re going to starve.” (laughs) It was okay. But when I was about to go to college, that was a critical decision. And so they said, “Well, you could still pursue art but if you could do commercial art—which was the term before, now it’s graphic art—then you could still do art and earn something.” It’s more of the practicality. But of course, when I was taking classes at UP—I did major in editorial design, but at the same time was taking fine arts courses: sculpture, painting. Printmaking was actually an elective requirement. Printmaking was actually just.... I only took it once, and I thought, ok I met the graphic arts requirement. So then the next semester—this is a very important story (laughs)—I was lining up to pay my tuition at the administration. And then Ofie Gelvezon [Ofelia Gelvezon-Téqui] went up the spiral staircase and saw me lining up down there. And she said, “Inday! Did you take Advance Printmaking?” I said no. She said, “Take it!” There was still room to add three more units. So ok, when I paid, I added Advance Printmaking.

Kiko She was the instructor of Advance Printmaking?

Ileana Yes, it was her second semester. It was a new course. UP got the press from the Ford Foundation. And then, I’m not sure if they sent Ofie to Italy for that—but Ofie learned printmaking in Italy and came back and opened that course. So I remember, the first course, there were the seniors. And when the second semester came, it was our batch, we took basic printmaking.

Kiko Lucky you were able to take those classes.

Ileana Yeah, but the second time she convinced me to take that course, it hooked me, so much so that even after graduating from editorial design, I was still printing. I was like, “Oh! This is a difficult process.” (laughs) It challenged me to... “I’m gonna work. I’m gonna get it.” It’s good they allowed me to work there. I was still printing and some students told me “Haven’t you graduated already?” (laughs) I said yes... Some of my classmates were already looking for jobs but I was still printing. I don’t know.

Graphony in Vermillon, etching, 1979

Kiko In 1985, you staged First Performance in which you alternatingly counted numbers in English and Spanish.

Ileana Oh when was that? (laughs) I’m getting old.

Kiko It was in 1985. I’m curious how far apart or close for you are the concerns of language with those of the visual arts for example? Or sound or performance?

Ileana Yeah, I think even some of my prints even have that sound reference, or music. When I create, sometimes I think... so even the use of the “counterpoint” term.... I compare it to a multiple... you know, like baroque music which is polyphonic. So I had that reference for my print: sound.

I had this print that had a layer of shapes. The other shapes that I constantly used were these elliptical shapes. So I had those color chine-collé and I compared them to music. Did you know those early prints I had with graphony? Have you seen those? The etchings?

Kiko I don’t think I have.

Ileana The actually refer to sound.

Kiko These were the ones from the ‘70s?

Ileana Yeah. So performance is just part of it. Because I was also attracted to filmmaking. Actually, my undergraduate thesis was an animation. And Mr. Larry Alcala was my teacher, the cartoonist. Remember him?

Kiko Yes!

Ileana So I did an animation. Super-8. I don’t know if it’s still around because I submitted that to the Chamber Film, our group.

Kiko The UP Chamber Film Group.

Ileana Yes. And I submitted that Super-8 and I forgot to get it back. For a while there was somebody at the Film Institute who said that she had seen that film.

Kiko I hope they have a copy still.

Ileana That’s only one copy I had.

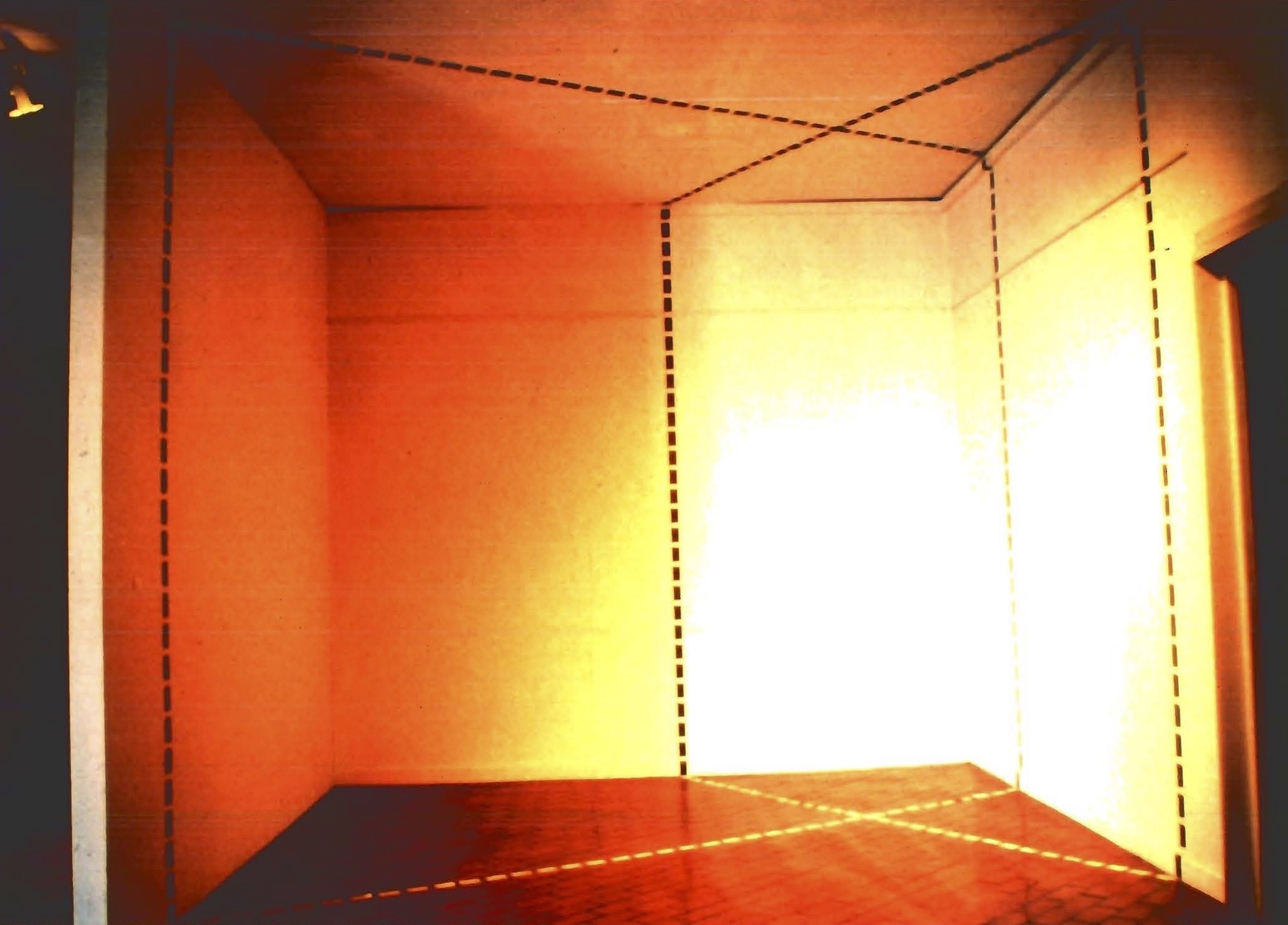

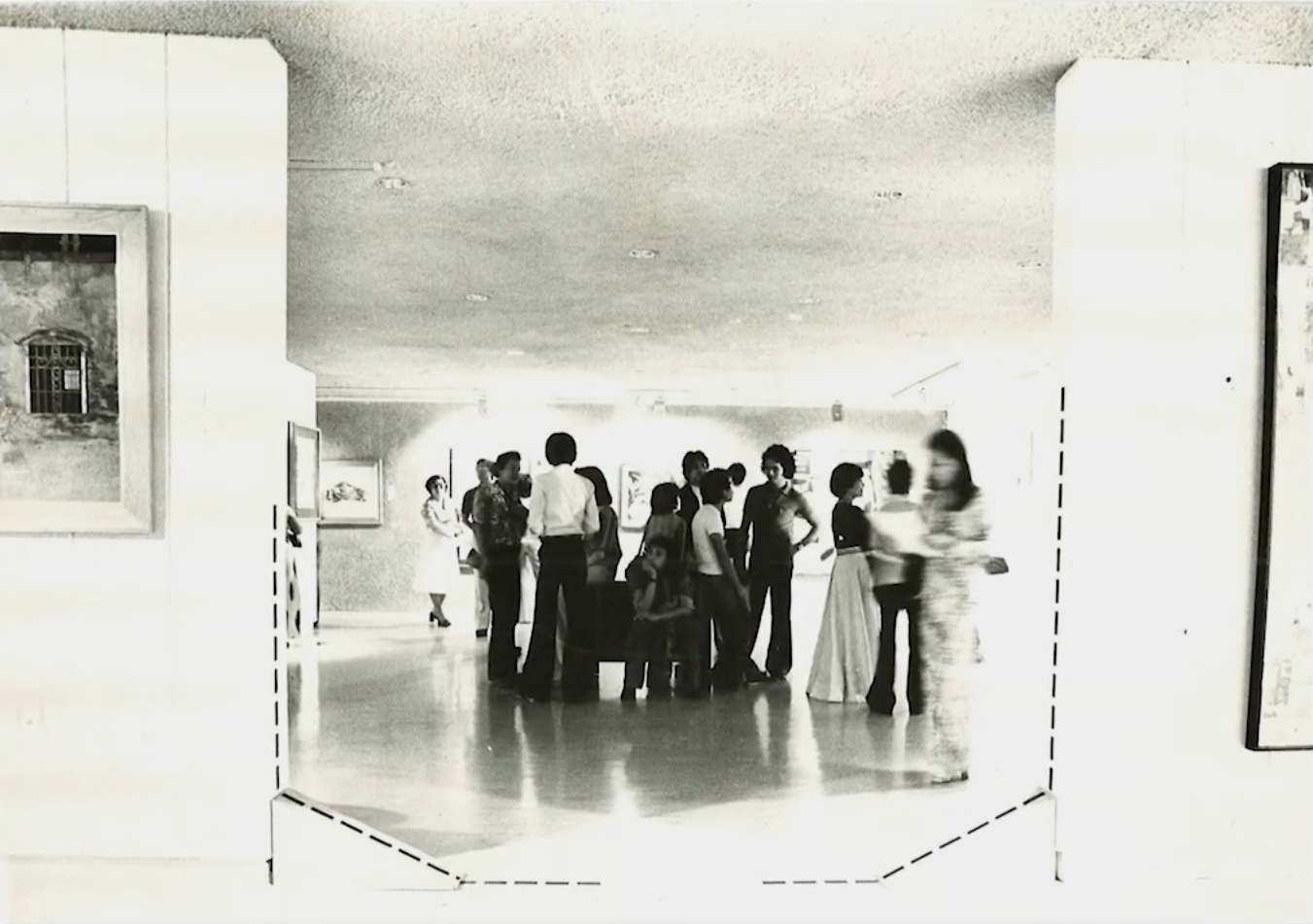

Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1976

Kiko In addition to Light Pores, you also made The Sun-Dial Constructions for the CCP [Cultural Center of the Philippines] 1976 Thirteen Artists Award. I now also recall Susan Dallas-Swann who was your professor at Ohio State, and her light installations. What do you find striking about light?

Ileana Wait, wait, wait. I did a performance piece with Susan Dallas-Swann. It was for a mixed media course. I used a bare bulb that was hanging from the ceiling and I would swing it so that the shadow would bounce from one corner… ‘Cause I used the corner of the room and then I would swing the bulb and the shadow would bounce from wall to wall. And I was reciting a poem by Joy Dayrit, my friend.

Kiko It seems that it recurs in a lot of your works, the trope of luminescence.

Ileana I’m not sure what it is. I think it’s well, because…. I think it’s because I come from the tropics, I don’t know. There’s so much of the bright light. Sometimes I used to look out. We used to live in Maginhawa in UP Village. We had plants around a small garden in front. We planted those crotons, with the multicolored leaves. And sometimes I just stared outside and those reflections of light… especially at high noon. But I remember when I was small, I would be by the window and just look out. And even now, that light, there’s a certain light of the day—even here in Hawaii—that reminds me of that feeling when I was small staring out the window. Light has that effect, I don’t know, it can make me recall certain things I’ve seen before or experienced. Or even rain, the feeling of rain, the dampness, the dark clouds and everything. Sometimes it hits that particular light of day that I think, “Yeah I remember that feeling.”

Kiko That’s quite evocative.

Ileana Yeah, and then it creates that feeling.

Kiko How would you describe that feeling?

Ileana Just like… it brings you back to that time when you were just staring at the rain or just feeling that particular day. One time I was in Berkeley, I took a train to the other side of the hill. There’s the hill, and the train goes to the opposite side. When I was travelling, I noticed the light changing. I was just staring out the window, but somehow, there was a different light in the area. I sensed that… that particular light.

Kiko This was in Berkeley you said? In California? Did you live there?

Ileana Yeah, I lived in Berkeley for almost ten years. So after Ohio, I moved to my cousin’s in Chicago but I didn’t have access to anything. It was in a suburb; I could not even walk. It was all busy streets. So I applied to the Kala [Art] Institute… and that’s when I moved to California.

Kiko And you stayed there before moving to Honolulu?

Ileana To Big Island first. I lived there for ten years and finally I said I would move to Honolulu so I could meet other printmakers here.

Kiko You had a pretty mobile life, having lived in all these places. What has been the significance or perhaps even the consequences of these physical journeys and constant relocation?

Ileana It was partly because… that was the recession. It was financial. I could not find work and nobody was really hiring. There was a lot of joblessness. And so I was talking to this artist [Setsuko Morinoue], she’s a potter, the wife of Hiroki Morinoue at Big Island. And she said, “Well maybe you want to move here?” So I thought maybe I could change my luck. I’ve been staying in Berkeley for more than ten years and it seemed like it was getting difficult to survive there. Although I had a studio at that time but so I just decided: maybe if I moved places, I could change my luck. (laughs)

Kiko Yeah, it’s all about luck.

Ileana (laughs)

Kiko You go where the luck is, right? (laughs) Do you ever feel like you’ve ever integrated into or settled in the places you’ve lived in? Or—I’m using your words here—have you “fused yourself to the conditions around you?”

Ileana I notice that when I move to a place, I cannot create easily. I have to settle first really well, maybe a year or two. Then I start to create, but if I… that’s why I never applied for residences because you’re just there for a month or two. I cannot create… my friends convince me but… some people can just go to places and just make but me, I don’t know, I just cannot.

Kiko Why do you think it takes a while for you to adjust?

Ileana I don’t know. Maybe I have to be settled down. All my things should be settled down. Then, I could start thinking about other stuff, besides just… you know…

Kiko And while we’re on the topic of movement: I remember a 1977 work of yours, The Steps. And you have described this etching to have “lent itself to much evocation.” How does one do this, lend oneself to much evocation?

Ileana You know I lived in the National Arts Center, remember? I taught there for a year in the Visual Arts.

Kiko Right, in Los Baños.

Ileana Those steps were the steps leading to the cafeteria. You walked up, you walked down, and then you would see the crocodile lake down there.

Kiko You found those steps to be striking.

Ileana And also that was the time when I was having this film interest. So it had that filmic quality to it, because it was a sequential image. At that time, I had those prints which had sequences.

Well, you know, if you as an audience look at the print. You go through a certain… you visually follow it, literally, by walking through it. As the audience, it might have an effect for you or you might recall something. Perhaps the process of tracing the image. It could be like that.

Kiko You yourself were a member of the UP Chamber Film Group. Can you tell me more about your interest in film in connection to, not just your printmaking practice, but also your conceptual practice?

Ileana At first when I was involved in the group, I was thinking of really going into film. But as a group, we met, we did some stuff together. But then I got frustrated with people coming in late. (laughs) And I thought, if I were involved in film, I would need to deal with all these different people. If I just made my prints, I could deliver and make it right away. (laughs) Because film needs a lot of people. So for me it became not manageable. And I wanted a result when making something. So I thought, maybe I’d just do printmaking. I would have more control.

![]()

Squaring II, etching, 1985

Kiko Would you agree that you were able to transpose the grammar or language of cinema into some of your prints?

Ileana Yeah, some of it. Especially The Steps. There’s movement all the time and even if I made prints… I had that one solo show in which I used a square plate. So a square has equal sides, yeah? So I would print one side and then ink it again and print the second side on the same spot. So it was spinning in place. So that was the idea. I call it “squaring” but it’s like… as you layer, it becomes a complex image.

Kiko Film moves a lot into your printmaking practice.

Ileana Yeah, in a way. And also the process in printmaking, there are steps. So you can always recover the plate, add some markings, making proofs, and if you’re not satisfied you can always come back and add some more. I took advantage of that process. I could integrate the process to the image. It creates that kind of imagery, but at the same time it’s the process that is integrated into the image. I also use this kind of shell, it’s a trochus shell (points to a shell in her studio). This shell was around the house when I was small. Because my aunt, she was a botanist. She teaches botany. She had some shells because she collected them because they went to this island in Mindoro, it’s like a marine biology station. Anyway, she had some shells at home. And I remember this shell was lying around the house. Until now I use that kind of trochus and I played with that too in terms of my prints.

Kiko It now makes sense, your interest in the environment.

Ileana Yeah, and I would remember in Bacolod there’s that resort area, Mambukal, that has waterfalls. We would sometimes go there as a family and we would hike to the first falls and my aunt would say, “Ok, as you go up there, collect this fungus that grows on the rotten log or tree.” She would give us samples. “When you see that, go collect it.” So we collected it for her. That made me aware of plants and my surroundings. Sometimes she would say, “Look at this tree,” she would point it to us, “that’s unusual for the markings,” or whatever. And we would look at it and it was embedded there while was I was growing up.

Kiko Was she your mother’s sister?

Ileana Yeah, my mother’s sister, Magdalena Chua. She also went to UP Diliman. She graduated from— took Botany. She and my mother were half-Chinese, half-Filipino. And my father is pure. So I’m actually ¾ Chinese.

Kiko Since we’re discussing movement still. This trope was also touched on by the late Raymundo Albano, for example in Step on the Sand and Make Footprints. And in one review of an exhibition of yours, Ray had expressed an admiration for your philosophical and idiosyncratic procedures in printmaking. I’m curious about your relationship with Ray as well as your common apprenticeship under Roberto Chabet.

Ileana Well, I think Bobby [Roberto Chabet] had a strong influence on us. When we were taking his class, we were so excited. We did a lot of experimentation and he let us think of ideas. We could present in class. It’s good that we had a teacher like that who was more open. It wasn’t like “Ok this is how you do it.” Because at that time conceptualism was also ongoing. So I think partly that and… that’s why we played around. We were not restricted or confined to a particular way. He encouraged us to do different things. That was another entry way that was wide open for us. Not to be limited to a particular medium, is very important.

Kiko And going back to the trope of the step, you had this work which you made for the Tokyo Biennale which you titled The Great Top Totem. It was a xerograph based on a photo you took of the San Sebastian Church’s spiral staircase. Do you consider yourself—

Ileana My religious background? (laughs) Well I’m Catholic, yes.

Kiko Do you practice?

Ileana Well, we went to church that time. But when I moved here, I lessened going to church. I mean I still believe in God or whatever but my sisters are more religious. They go to church every Sunday, celebrate whatever occasion. Me, I don’t do much of that here. I don’t go every Sunday. But yeah, my high school was a Catholic school. It was a Recollect-run university: the University of Negros Occidental-Recoletos.

Kiko That was in Bacolod?

Ileana Yeah in Bacolod. It was a university run by Spaniard priests.

Kiko With regards to this work though, The Great Top Totem, you described it to be a “step-like” vision. I noticed that the idea of a step, and perhaps this is again related to film, is very much present in your print works during this period.

Ileana Actually it’s a xerox on which I stuck the image to the top. And then the top has a light.

Kiko Why this staircase in particular?

Ileana I don’t know. I was going around and taking pictures at that time. I don’t know why I went to the church. It was dark actually. So sometimes you just instantly take a shot. And then eventually, it ended up in that show. I don’t know if I was thinking of finding something or it just so happened that it was a picture.

Kiko You’re back in the studio now, in Honolulu. What do you like about working in a space that is focused primarily on studio graphic arts? And how might this support or oppose your insistence for artists to go beyond the boundaries of media forms?

Ileana Sorry, can you repeat?

Kiko Does working in a printmaking studio hinder you from exploring various media?

Ileana Oh. A studio is really important. When I retired after the pandemic—I was forced to retire at 70. At 69, the pandemic happened. And so my day job was working at the Montessori school for kids. I decided to just retire. So then, I moved to a senior house. The senior houses here are small studio apartments. You have a space for the bed, to eat, a little kitchen with a little stove, a shower, a bathroom, in that one space. I was thinking, “Boy, I need a studio now.” Because I was retired. I wanted to work. I needed a space. For me, space is important. When I work, I have that space because sometimes I go big. Like in Berkeley, I was happy that I got that studio, because I could lay down wood, pieces of… I did little furniture. I could measure, do things longer. Two years after, I kept applying. This building is an artist studio. It was designed for artists. It was a lottery, I wasn’t lucky. Finally, after three years, I was able to get this space. I moved just last December.

Kiko Where is it?

Ileana This is in Kaka’ako in Honolulu. Now I have a bigger space, I’m happy. It’s important to have space. Although I go to the shop because I don’t own a press. I still have to go to Honolulu Printmakers because the press is there. And the people—you can talk to the other artists, it’s important.

Kiko I wonder if you had the same experience at the PAP [Philippine Association of Printmakers]? Can you name the artists and writers with whom you enjoyed working in the past?

Ileana I didn’t really print in the PAP. I was a member but I worked at UP because during that time, even if I’ve graduated already, they allowed me to work—so I could still borrow the handle. And the press was open, it was in the hallway, so I as long as you got the handle, and the pin that you can crank, and the blanket from the office, they allowed you to work. So it was good. During that time I was printing there. Not at PAP because I was in Quezon City and PAP was in Mabini, it was far.

Kiko Who else were there at the time?

Ileana There was Orland Castrillo, the president I think. There was, ok the women, the owner of that place was Adele Arevalo. And then there were women like, she’s from Baguio—Rhoda Recto. There were—if you look at the older printmakers like Jess [Flores]…

Kiko Ayco?

Ileana Zaragoza? The woodcut artist?

Kiko Efren?

Ileana Yeah, Efren Zaragoza. There was this young guy, he died. Lito Mayo was there.

Kiko I love Lito Mayo.

Ileana There was this writer who did prints. (pause)

Kiko Rodolfo Paras-Perez?

Ileana Paras was not yet there. But he finally taught at UP when I was still there. I took one class, art history, from him. But yeah, Jess (long pause)—

Kiko Anyway, it’s fine.

Ileana Yeah, you’ll see.

Kiko Is being different or unique something you work towards?

Ileana Not really. When I work, I just know that it comes from my own source. Or my own interests. Those are my motivations. Not necessarily very conscious of making something unique or different. Not really. It’s just whatever comes, I deal with it and that’s it. And I know that each individual is unique anyway so if another artist approaches printmaking it’s because of her or his own particular person. I believe in that.

Kiko When I look at your work, I think of the idea of the impression which has strong evocations in both the graphic and conceptual. When you say impression, it could be like a print, or a thought-feeling, or like an activity. Do you ever think of an impression this way?

Ileana Well (long pause) not really. When I think of an idea, it’s an idea, and then I would look at it. Is it best articulated in print or is it best articulated in video, in a moving medium? Or is it best articulated in a sculpture, in a three-dimensional thing? I have that sort of thinking when I have an idea. And I think, “This may be presented in this medium than that medium.” I have that leeway to choose from. And since I’m handy, I can fix [things]. I also took classes in—I didn’t really mean it—but before when I was small, I did little hammering, fixing in the house. And so when I went to the UP—actually when we had our silkscreen—I had to build my own frames. So I started buying wood, make my own frame, stretch my own silk. So then I started little chair at home. And so when I was in Berkeley, one day I thought, “Hmm, maybe I should learn more joinery, the formal way.” So I went to the community college, I took a summer class. The assignment was a shaker table. Then they teach you safety, because you deal with table saw, joiner, whatever, band saw. When you pass that, then you learn the process of basic mortise and tenon. But instead, I said, “No, I’m not gonna make a shaker. I’ll make my own table.” So I made my own table. Since I had an art background, I could design my own. Some people didn’t have that background. So I made my own first table. I put a stone on top. In Berkeley, I lived near the railroad track and there were stones on the track. So I went to the track and collected flat stones and I carved the table top and embedded the stone on the wood. That was my first table.

Kiko Would you say that—it seems that you like found objects—

Ileana Yeah, whatever is around.

Kiko Would you say this ties with your experiences with your aunt who was a botanist, asking you to source objects from the forest for example?

Ileana

Yeah, well that’s part of it. And where we used to live—our house in Bacolod was near a creek. There was a creek and a bridge. And then the upstairs there was the owner of the hardware store. We were renting the lower part of the house. You know the crates from the hardware store? They were crated. They would dump them on a little space in front of the house. So that’s why I am also attached to wood, because when we were small, there were these crates, and the nails were sticking out too, and all these shipping shavings, were cushioned. And we played house on those crates sometimes. Because they were squares open on one side. We would make houses there, we would play. Wood is also important because I was exposed to the palo china, those pinewood—around us—and we went to those resorts with those stones. It’s just rich in things, around you.

![]()

Wedge, masking tape

Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1977

Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1977

Fukuoka Art Museum, 1980,

Museum of Philippine Art, 1980,

& Pinaglabanan Galleries, 1986

Kiko You also have this—your use of strips of masking tape which you’ve casted or made to crawl on walls, for instance—there were various exhibits—mounted in the CCP Main Gallery in 1977—

Ileana Yeah, it was more of an architectural piece. It depended on the floor wall and ceiling. That particular piece was supposed to be—do you know the Shop 6 group? They were students of Chabet. We would go to [Sining] Kamalig, and then there was an available shop space where the owner, Ledesma [Corita Kalaw], allowed the artists to use it for the meantime that it was vacant. That was part of my project. I was making drawings of that, dotted lines. But I was not able to do that in Shop 6, because by then someone had rented that space.

Kiko You’ve also exhibited them in Fukuoka Art Museum in 1980 and also in Pinaglabanan.

Ileana In MOPA.

Kiko MOPA?

Ileana I did one in Fukuoka and one in MOPA, the Museum of Philippine Art, near the embassy. But they closed that museum, but it was a nice building, a two-story site. For awhile they had exhibitions there. The one I did was on the second floor. So I told Ray—I said I needed a wall—because there was kind of angle, a wall that was L-shaped—and if they enclosed this L-shape, it becomes a room or an alcove, then I could do my tapes. So they did build a wall and I started building. [Arturo] Luz was there. I remember I was taping this and Luz came by.

Kiko These installations of yours have led some to believe that you were driving at a feminist statement.

Ileana No, I wasn’t really thinking of that, I was thinking of the spatial illusion of lines and how it can create that sort of suggestive partition of space. It was more of that.

Kiko And you fashioned them to be dotted instead, for example—

Ileana A solid line?

Kiko Yeah, a solid line.

Ileana Oh, I don’t know. I just thought—It would just be a suggestion. If you put a solid line, it’s a definite division. But if dotted, it’s more suggestive. And then at least as a viewer, you would be like, “Was she trying to do something here?” At least it had that ambivalence in a way.

Kiko You once wrote of the importance of the awareness of how “critical pieces will situate themselves in space.” Do you think works of art are critical by themselves?

Ileana Critical of what? Sometimes I think when you do something, it would have that effect. But I think it would hit something sometimes. You just put it up there but somehow it might create something, or suggest something.

Kiko Did you ever think of them in terms of addressing certain issues?

Ileana I don’t know. Sometimes, for example with the pixelated images. I was saying something there. But sometimes, they are also just imagery. They may not be intended to be critical. But as a viewer you might see that she was saying something more than what the work might suggest.

![]()

![]() The Bamboo Swing, bamboo, wood, string

The Bamboo Swing, bamboo, wood, string

Pinaglabanan Galleries, 1984 & 1985

![]()

Pond, bamboo, red wood, string, videoKala Art Institute, 1989

Kiko I wanted to talk about your work Pond, which had the earlier title of The Leaning Sculpture/The Bamboo Swing from ‘84. How has the concept of this installation work changed over time?

Ileana You see, sometimes an early work would just be there and then all of a sudden, they crop up. The Kala Institute had this biannual. They asked artists to make proposals. And if they accepted your work, they give you some grant, and then you can do the project. I saw that announcement, Seeing Time series. It was a multimedia thing—you could be a performer, a musician, whoever, whatever medium, you can submit. I thought “Maybe I could develop the swinging thing that I did before.” So I started creating and planning and I did an installation and then I put some video around the gallery. Bamboo was the available material in the Philippines. In California—red wood is indigenous to California. I borrowed a camera. At UC Berkeley, they had classes at the Student Union. You didn’t have to be a student there, but they offered classes. They had pottery, video classes. They had equipment there. I took a class so that I could borrow the equipment. I just went outside the campus, borrowed the tripod and videoed the clouds. It was a nice day, I just pointed the camera to the sky and just let it run. So there were two different images. I put those four monitors on the four sides of the gallery and so when you looked around, you would see these clouds moving, slowly, naturally. And they asked me to title it. At first there was no title. Anyway, I thought, “Oh okay, maybe I’d title it Pond.” Because the swinging poles in the gallery space, in the middle, they were randomly installed. They likened to several stones thrown into the still water. It had ripples.

Kiko Your work oftentimes evokes the accidental, for example with the clouds. Do you accept randomness to be true?

Ileana It depends. Sometimes the idea would just come. I don’t know why I thought of the clouds. But I thought, the world was like spinning too, everything was spinning. So I thought the clouds would be the best subject. You don’t know anything and then you see something moving slowly. It could be the environment that could fit the sculpture. Also thoughts, they come randomly too. They trigger something. Or words sometimes. That I think comes from your environment. It’s not that I create it. It just so happens that it’s accidental.

Kiko If the idea enters through the environment, as you said, do you think your encounter, or you noticing the thing from the environment, is all up to chance? Or is that encounter a coincidence for you?

Ileana It could be both. That instance when I was just staring out the window. It just so happened the time was right. Could be. By seeing it, or if somebody said something, it could trigger something in my mind. It’s everywhere anyway. It’s around you. Sometimes you just react to it or accept it or recognize that, “Oh I didn’t intend to do that but because I made a mistake, maybe I could do something with it.” So it just all happens.

Kiko Your work Pulp and String, from 1980—

Ileana The what?

Kiko Pulp and String

—

Ileana Oh! That one.

Kiko —from the CCP Collection. I’m not sure if you’ve seen the video but it has been annotated by Patrick Flores as—

Ileana Yeah, I saw the video.

Kiko —a “Series of turns in becoming and unbecoming.” How did the work come about?

Ileana So that time, I was making paper. I would collect things around the house. Along the side of our fence, I would collect it and would just make pulp. And then, I was thinking of the deckle. You know the deckle?

Kiko Yes.

Ileana When you make paper, there’s a deckle. There’s the frame and there’s the slatted thing where you scoop the pulp, to catch the pulp to form paper. That whole idea—you see this is another way I am pointing at here—process can also create the imagery. The deckle for me was the idea of a frame. And so, creating the frame and making a simulation of the strings like the deckle, would be a good way to make a work. So sometimes it’s the integration of the process and the tools you use. Just like when I use the process in printmaking to suggest one thing. I sometimes use that to my advantage to create something.

Kiko So there’s that idea of the becoming of a work of art, and there’s also the idea of unbecoming.

Ileana I don’t know about that part. That I cannot predict. Sometimes work has that potential: once you put it out, it creates something else.

Interview: May 10, 2023

Honolulu & Mexico City via Zoom

images © Ileana Lee

Honolulu & Mexico City via Zoom

images © Ileana Lee

The Bamboo Swing, bamboo, wood, string

The Bamboo Swing, bamboo, wood, string